The idea of the "New Vegetarian/Vegan Movement in China in the 2010s" is a hypothesis that I would like to propose. (Given the fact that there are no distictive words in the Chinese language dedicated to vegetarian vs. vegan, both words are used interchangeably in this essay.) It is based on two facts. First, as a symbol of the vegetarian movement, "vegetarianism" is often regarded as the opposite of the "meat-eating diet" (or what we call the "animal source diet" after 2010). Vegetarianism is not just a "regimen" or "Sādhanā"; rather, it is where paths to well-being, nutrition and health, environmental conservation, social justice, agricultural production, food security and more converge. It forms a distinctive community, characterized by the practice and promotion of "vegetarian lifestyle" (rather than an affiliation with Buddhist groups, etc.). For these reasons, I believe that none of the claims for vegetarian diets in China risen from different periods of Chinese history or the plant-based diets driven by Chinese classic thoughts or economic incentives meet the standard of "vegetarian movement". The development of the vegetarianism in the 2010s, however, is qualified.

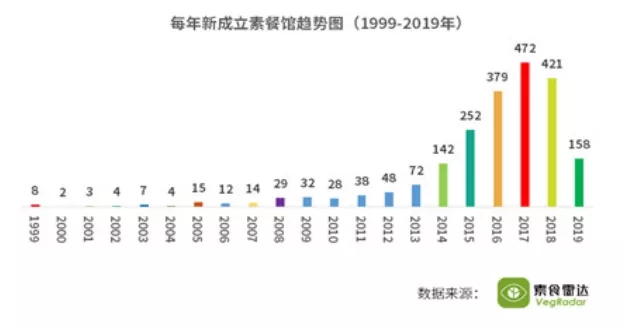

In the 2010s, media about vegetarian/vegan diets became popular; and among them, the most popular WeChat official account draws over 300,000 "fans". These We-Media, which took advantage of the Internet, constituted a powerful force in promoting the vegetarian movement throughout society. At the same time, the number of vegetarian restaurants in China was growing at an unprecedented rate, reaching 2,224 in mainland China as of October 2019 (according to "VegRadar" data). The growth rate in the 2010s increased by a dozen times (as seen in the chart below).

Behind this wave of vegetarian movement in Chinese mainland are mostly people who were exposed to food issues around 2009 and became leaders of the vegetarian movement in the 2010s. The movement was inspired and influenced by Western researches on nutrition, public health, environmental science, animal ethics, agroecology, as well as the popular culture of anti-consumerism. With the latest Western evidence-based scientific findings and Internet media, the movement opposes the industrial meat production and consumption that originated in the West and grew rapidly in China. Integrating the elements of contemporary spiritual pursuit, “the national craze for learning Chinese traditions” and cultural conservatism, the movement seeks to go beyond the religious discourse and construct a new system of popular discourse between post-industrial thoughts and the traditional culture.

Second, the "newness" of this vegetarian movement is relative to the “oldness”of the first Chinese vegetarian movement, which started in the 1910s, the transitional period between the Qing dynasty and the Republic of China. Interestingly enough, despite the exactly 100-year time difference, the two movements face similar opportunities and challenges - especially the discourses they tried to go beyond and construct. Nonetheless, they responded to the calls of their eras differently.

The pioneers of the first modern vegetarian movement in the 1910s - represented by Wu Tingfang and Sun Yat-sen - could hardly imagine that it would take a full 100 years for their ideas and practices to be endorsed and practiced by the "post-70s", "post-80s" and "post-90s" generations in the People's Republic of China. Despite many similarities, the two movements differ in two aspects. First, the movement in the 1910s is driven by the elite politicians, revolutionaries, and businessmen of the time, while the second movement is led by common people. Secondly, the first generation of vegetarian activists in the late Qing dynasty are concerned with the establishment of modern state and the transformation of national character, making their state invincible in the international competition that was a zero sum game. In this sense, they and their opponents (who believed that the vegetarian tradition shall be held responsible for the nation’s underdevelopment) were two sides of the same coin.

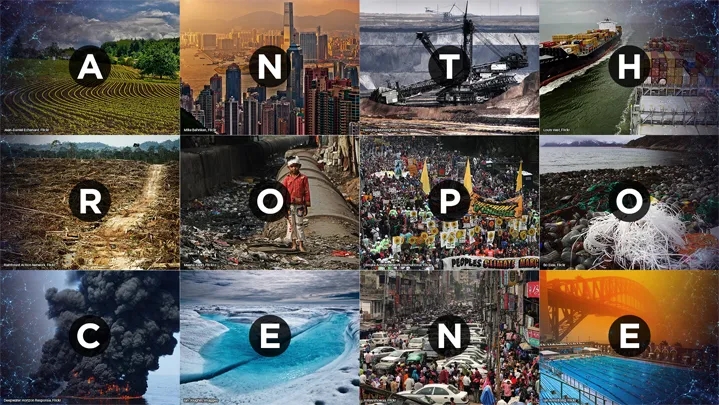

Comparatively, the second movement took place in the 2010s, a time when China established the world's largest industrial production system, and became the world's second largest economy and the world's largest producer and consumer of food. This movement could be understood as a response to the growingly prominent downside of consumerism, the global health crisis and the ecological degradation of the Anthropocene. To a certain extent, the movement echoes the national strategies of the time, such as the "Construction of Ecological Civilization" and the "Community of Shared Future for Mankind", etc. Therefore, the essence of the new movement is to seek universal values of mankind, cooperation for a win-win outcome rather than competition among the states, which was reflected in the old movement in the 1910s. Whether the moment in actual operation would deviate from its goal is up to all stakeholders in the movement. In reminiscence of the first vegetarian movement that aborted in the 1930s and 1940s and its leaders' vision of reviving the nation, which nonetheless experienced more hardships in the following years, we cannot help feeling pitiful. The destiny of the second vegetarian movement is to be unfolded in the years to come. In this sense, the second vegetarian movement not only matters for the survival and competitiveness of the Chinese culture and the nation, but is also crucial to the human civilization as a whole.

This article is not aimed at being "neutral", "objective" or "comprehensive". Using a first-person perspective, this article reviews the development of the new vegetarian movement in mainland China in the 2010s, reflects upon its successes and failures, and projects the future of the movement.

The vegetarian diet becomes "vegetarianism" because of influence from globalization. Angela Ki Che Leung, a scholar of history in the University of Hong Kong, notes in her paper To Build or to Transform Vegetarian China that "vegetarian" in the traditional Chinese society, for the scholar-official class, means food that promotes “lightness" of the body and soul , and beneficial to health. Although that type of vegetarian food mainly consists of vegetables, the diet does not entirely exclude meat. Outside of the context of Buddhism, Chinese language does not differentiate plant-based foods and the animal source foods . In comparison, in Western society, the binary classification of plant-based and animal source foods has existed for a long time. From Pythagoras in ancient Greece to ancient Rome and then to Arabia, there is a rejection of meat that is not motivated by religious beliefs, but on the grounds of people’s physical and mental well-being as well as bioethics. In the India Subcontinent, differences have been drawn between "Su” (plant-based food) and “Xing” (animal sourced food) for a long time, dating back to over 3,000 years BC. In the Indian caste system, the upper-caste advocates for harmlessness and non-violence (ahiṃsā), and think that meat would harm one’s physical and mental health. Jainism and Buddhism, also originated in India, developed the classification between food of plant origin and food of animal origin one step further.

In Western society, vegetarian diet did not become "vegetarianism" until the 19th century. The change in vocabulary reflects the development of social thoughts. The term "Vegetarian" was invented in 1849, combining "vegetable" and “supporters”(i.e. –arian). Regarding the “-ism“ in the Vegetarianism, in The First Lecture of Nationalism, Sun Yat-sen states: "ism is a thought, a belief, and a power. Once human beings try to understand the truths, they will engender thoughts. Once the thoughts come into existence, they will have a belief, and with a belief there comes power. Thus, it is well established that the ism develops from thought to belief, and then to power, and eventually it stands." Thus, when the practice of vegetarian grows into vegetarianism, it develops its own system of thoughts, instead of moving towards the opposite direction, ideas about nutrition and health, spiritual meditation, bioethics, and ecological sustainability all become parts of this system. Such self-consistent ideology is quite different from the "Su" of the scholars in the traditional Chinese society and the "cleanliness" derived from the "quit killing" in Chinese Buddhism.

Reflecting upon the two vegetarian movements in China in the 1910s and the 2010s, we can see that both resonate with the spread of vegetarianism around the world. The promoters of the 1910s, led by Wu Tingfang, Sun Yat-sen, Li Shizeng, and the Jian Brothers of Nanyang Tobacco Company, all had strong international backgrounds. They adopted the language of the Western modern "science" to explain food, nutrition, and health, transforming the connotation of“vegetarian” into the counterpart of meat-eating, and thus a source to build new body and for the establishment of a modern state. In Strategies for the Founding of a Nation, Sun Yat-sen even says, "the evolution of Chinese modern civilization fell behind in many ways, but the advancement of cuisine is still beyond the reach of other civilized countries." He also adds that "the Chinese dietary habits are comparable with the latest scientific theories, which were proposed by the most brilliant medical scientists in Europe and the United States today.” He advocates for placing limitation on meat consumption, and praises that “vegetarian diet is a magic tool for prolonging lifespan, which has already been acknowledged by scientists, medical scholars, physiologists and doctors. Chinese vegetarian diet is particularly suitable. Notably, tofu should be treated as meat, and its consumption should not exceed the amount needed by the body, for the sake of hygiene."

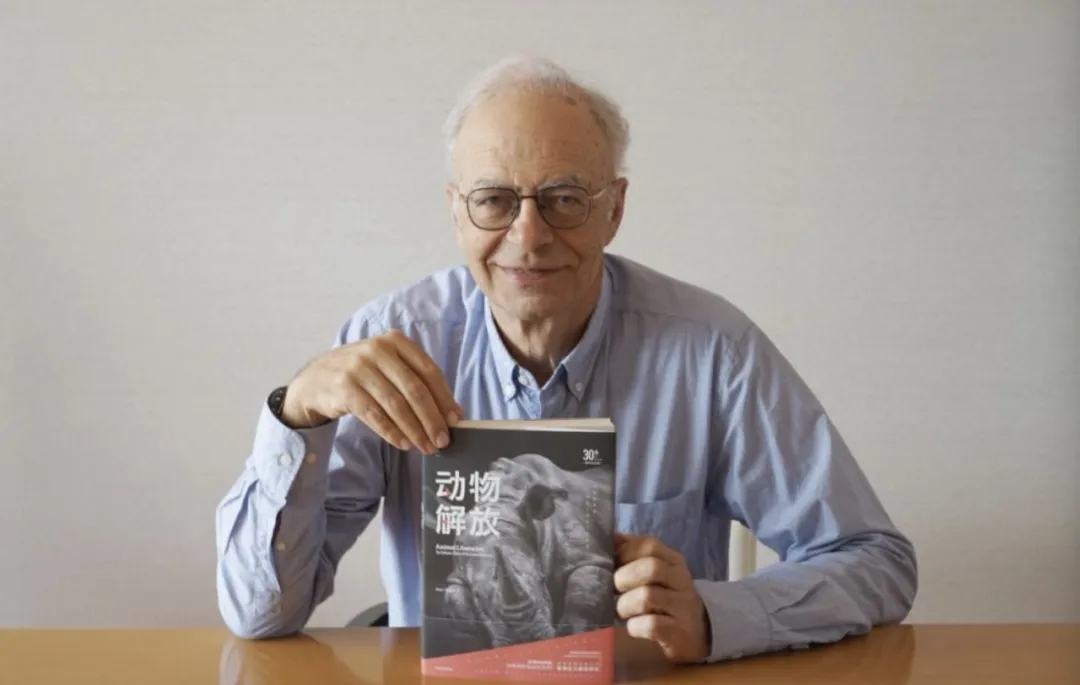

The Chinese vegetarian movement in the 2020s also has solid international connections. Like the first vegetarian movement led by pioneers such as Wu Tingfang, this second vegetarian movement was also aimed at going beyond the narrative of Buddhism and the circle of Buddhist believers, and seeking contemporary science and philosophy as theoretical basis. From a global perspective, two epoch-making books in the 1970s laid the foundation for the later vegetarian movement around the world. The first is Diet for a Small Planet (1971) by Frances Moore Lappé, with a circulation base of over 3 million copies. The book points out that the world hunger program is not caused by food scarcity, but is greatly related to meat production. Attempting to combine personal food therapy with social justice, this book becomes a pioneering work on environmental vegetarianism. In 1975, Peter Singer, the Australian philosopher graduated from the University of Oxford, published the book Animal Liberation, reflecting on the ethical dilemmas of the western industrialized farming system on the grounds of bioethics, making the concept of "Speciesism" (or Specism) created by the Oxford scholar Richard D. Ryder well-known. This second book thus becomes the theoretical basis in support of global animal liberation movement. The significance of this book lies in its breakthrough in traditional religious ideas (such as "compassion" from Mahayana Buddhism) or spiritual formation, and its integration of secular values into the course of caring animal lives.

However, during the 1970s to the 1980s, mainland China was still under the "Cultural Revolution" to the early stages of "Reform and Opening Up". By then, China had little connection with environmental ethics, bioethics, and anti-consumerism culture around the global. The priorities of agricultural production and public health are still high yield (quantity rather than quality) and the improvement of malnutrition ("getting fat" was a kind of compliment that signals an improvement of living standard in that era). The ills of consumerism, the double burden on health and ecology, along with the spread of the global vegetarian movement would only gradually unleash their influences until after the 2000s, a decade after the reform of market economy.

When I was filming the short documentary "What’s for dinner?”in 2009, I noticed an interesting phenomenon. Interviewees aged above 50 at the time coincidentally mentioned the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. The early 1980s was the period when televisions were introduced to ordinary Chinese households. With the improvement of China-US relations, the Chinese sports delegation participated in that Olympic Games. It was also through the live broadcast of the Olympic Games that enormous residents of small and medium-sized cities outside of Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, who had no chance to meet foreigners on the streets, saw the demeanor of foreign athletes: taller, faster and stronger. My interviewees were particularly impressed by the U.S. women's volleyball team, and exclaimed: Americans eat beef and drink milk, and thus they are tall, big and strong. But what Chinese residents failed to realize at that time was that the American athletes they saw in the Olympics could be very different from average Americans that we see on the streets in the United States, both in terms of their bodies and their health.

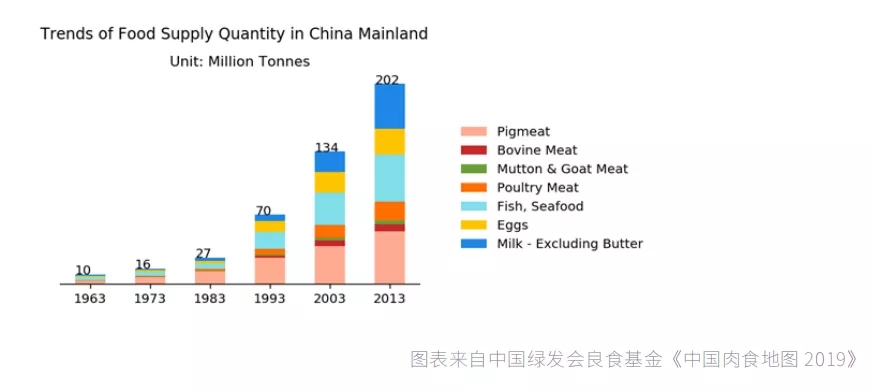

Equating taller and larger body with fitness and even healthiness overlooks some facts. For example, the famous American women's volleyball player Flo Hyman passed away at the beginning of 1986 – one and a half years after the Los Angeles Olympics – from a cardiovascular disease, triggered by Marfan Syndrome. Her extraordinary height complimented by my interviewees is a symptom of the Marfan syndrome. While this syndrome is known to be a genetic disease and has little to do with dietary choices, this story at least illustrates that being tall and being healthy are two different concepts. On the other hand, the slogan "A glass of milk strengthens a nation", which is said to be originated in Japan, is imbued with commercial demands and East Asians’century-long dream of modernization through strengthening the body. As the result, the advocates of this slogan behind the scene encourage the public to drink milk by the use European and American whites as evidence and even recruit them for advertisements. But what these advocates selectively ignore is that there is a longer history of drinking milk in this economically "underdeveloped" South Asian subcontinent, living by people with darker skin (Chinese dairy product advertisements have rarely used South Asian models or actors). They ignore the fact that drinking milk has never been a part of the tradition of Han people, nor do they mention the study of the strong positive correlation between the intake of milk-drinking and fracture rates done by western intellectuals (Walter Willet et al., Milk and Health) , which otherwise could have challenged the popular misunderstanding of the relationship between milk and health. In any case, once the "causality" between a diet rich in animal protein (featured with beef eating and milk drinking) and the stronger physique of Westerners is established, the economic growth brought by Reform and Opening Up will automatically engender a rapid growth of meat consumption and increasing scale of industrial breeding industry (as shown in the following chart "China Meat Atlas 2019" by the Good Food Fund of China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation).

In the 2000s, after a period of rapid economic development, the cost of environmental deterioration started to become obvious for China. The society's understanding of environmental issues has also developed. When the concept of "environmental protection" was first introduced to China from overseas in the 1990s, many people equated environmental protection with environmental sanitation, or urban sanitation, such as the absence of trash and phlegm on the ground. However, as the ecological environment deteriorated, an increasing number of people realized that environmental deterioration is a broader concept, or a structural issue, not just "hygiene". At the same time, there were changes in the field of public health: "hidden hunger" and the problem of overnutrition mainly caused by excessive meat consumption became remarkable; in addition, obesity, "three highs" and cancers caused by excessive meat consumption kept rising in the 2010s, constituting the major threat to public health. The impact of environmental degradation on public health was also salient - the environmental toxins in the air, water, land and even the food itself rise year by year, which in turn damages public health. Industrialized food production is featured with such interplay between environmental problem and health deterioration: food production is overly concentrated on efficiency, quantity and short-term supply capacity, while ignoring quality, long-term planning for agricultural resources and the impact of agricultural activities on the ecology, resulting in further burden on public health. Specifically, food nutrient decreases year by year, causing hidden hunger, and public health was also harmed by the environmental toxins caused by agricultural fertilizers and herbicides, as well as the antibiotics, hormones, and heavy metals from factory farms in turn harm the public health. Consequently, people increasingly distrust the existing food system.

Buddhism also ushered in a new period of development in the 2000s. In the history of Chinese Buddhism, the main body is the "mountain Buddhism" that retreats to the rural areas. In the new era, in response to rising demands, concepts "engaged Buddhism" and "urban Buddhism" emerged. But so far there is no complete missionary system like compared with Christianity’s. The innovation of audiovisual technology in the 2000s promoted this missionary work to some extent. The popularity of VCD (later replaced by DVD) players in Chinese households made the Buddhist lectures accessible to thousands of households, bypassing the restriction of time and space. Among the missionaries, the typical and the successful one is an old master of the Pure Land Sect of Chinese Buddhism in Taiwan. The video and audio of his lectures were used by many Chinese Buddhist monasteries and Buddhist families in Chinese mainland. This master also made a combination of the Pure Land teaching method and "traditional Chinese culture" and praised the "classics" of Han culture such as "Liao-Fan’s Four Lessons" and "Di Zi Gui" (Standards for being a Good Pupil and Child). Additionally, Buddhist monasteries have held “summer camps” and “meditation camps” since the mid-2000s to attract believers. These activities reached their peak in the 2010s and attracted a large number of believers for Buddhism, especially the young people who are looking for "spiritual sustenance" and meaning of life, as well as newly affluent population. The development of Buddhism during this period contributed to the subsequent vegetarian movement in the following two aspects:

First, the traditional Buddhist "mercy release" activities (i.e. free captive animals) have rapidly developed into large-scale industries. The main Buddhist preachers of this period, whether they were masters of Chinese Buddhism or the historically non-vegetarian Rinpoche and Khenpo of Tibetan Buddhism, almost spared no effort to promote "freeing life" and “non-killing” with a vegetarian diet as the main means. The negative effects of large-scale mercy releases on the environment and animal protection emerged quickly. Yet as one of the most effective means of contacting believers, if not prohibited by law (Taiwan has banned releases under the joint efforts of environmental protection and animal protection agencies.), it mainly depends on the self-restraint of various monasteries and spiritual groups. The opposition from environmental protection agencies and the self-discipline of Buddhist groups have made the vegetarianism as a more legitimate and reasonable way of freeing lives “on the dinner table” increasingly favorable.

Second, with the efforts of Buddhist groups and groups advocating "learning Chinese traditions" (originated from Taiwan), “the craze for learning Chinese traditions” gradually accumulated potentials in the late 2000s and in the early 2010s. The secular "learning Chinese traditions" and "promoting traditional lifestyle" have provided new spiritual endorsements to support some promoters of vegetarian movement beyond Buddhism, Western science and culture. In the 2010s, the economic strength and global influence of Chinese mainland became increasingly stronger. The craze for traditional Chinese classics not only met the populations ‘desire to find their own cultural identity, but also echoed the need of the Chinese state to export its "soft power". For non-Buddhists and vegetarians who hold doubts towards scientism and modern Western science, traditional culture represented by the Book of Changes, Huangdi Neijing, and Chinese Traditional Medicine equip them with new tools to express themsleves.

However, despite the simultaneous development of China’s new vegetarian movement and the development of Chinese Buddhism in the 2010s, like their ancestors in the 1910s, the new generation of promoters of the former chose to “decouple” vegetarianism from Buddhism and to keep a certain distance from religion, so as to allow the vegetarian diet to penetrate into thousands of households and become the choice of broader groups. Interestingly enough, in fact, some influential Buddhist masters deliberately “disconnect” Buddhism from vegetarianism in order to lower the “barrier of entry” for Buddhist studies, since vegetarianism could prevent the believers from “entering the door of Buddhism.” In 2015 at a Buddisht summer camp in a prestigious Chinese Buddhist monastery, after I screened the documentary "What's for dinner?" and introduced the contemporary vegetarian movement, the abbot of the monastery stood up and said to hundreds of audience that vegetarianism is not a necessity for the study of Buddhism.

At the same time, global vegetarianism also made new progress in the 2000s. In 2003, two major dietary and nutrition societies in North America issued blockbuster statements that "well-planned vegan diets" are "appropriate for individuals during all stages of the life cycle". Later, in 2005, the documentary "Earthlings" and the masterpiece by Cornell University nutrition professor, Dr. Colin Campbell's The China Study were released. They present videos and evidence for further academic study concerning the animal abuse by industrialized farms and the health benefits of plant-based diets (from then on, the concept of "plant-based diet" entered the Chinese language). Both became must-know pieces among promoters of China's new vegetarian movement at the beginning of 2010. The book Eating Animals (by Jonathan Safran Foer) was published in 2009, a 2011 documentary Forks over Knives and a 2014 documentary Cowspiracy have aroused much attention in the United States and other Western societies. Studies have shown that 70% of American vegetarians become vegetarians after watching a documentary. The influence of digital video recorders and film production in the 2000s in the promotion of the vegetarian movement is evident.

In contrast, Chinese documentary pay less attention to this field. Except for the documentary short film "What's for Dinner?", filmed in the middle of 2009, and the documentary series "Chinese Zodiac", which I started planning since 2016, documentary production and even book writing were absent in the Chinese New Vegetarian Movement in the 2010s. Assuming that every social movement has its own endorsement books and documentaries, throughout the 2010s, there was no book or documentary in Chinese mainland that influenced the public perception of the vegetarianism. I believe that the reasons behind it are as follows: on the one hand, food issues are not yet known to Chinese intellectuals, artisits, story-tellers, and even civil sociey activists; on the other hand, since the domestic academic circles have not produced much work in the relevant areas, the theoretical framework for writing and other creative production is very limited.

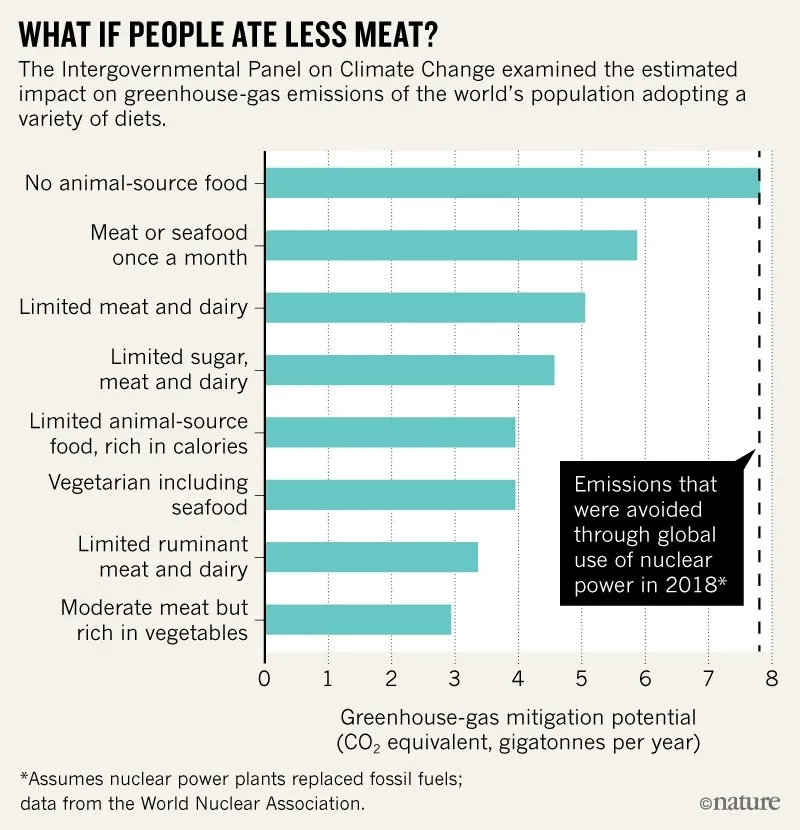

The expansion of the global vegetarian movement from 2000 to 2010 has an inseparable relationship with the advancement of global health research and environmental research, as well as the people’s increasing awareness of animal welfare. As early as the late 2000s, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recommended "eating less meat" as one of the three key actions to mitigate climate change. On August 8, 2019, the IPCC released a high-level report from more than 100 scientists across the world, clearly pointing out that the plant-based diet is one of the most important means for mankind to mitigate climate change (see the figure below).

The report also provided specific policy recommendations for the reduction of meat consumption. At the beginning of 2019, the famous "Lancet" magazine published the Food for the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Committee Report on Healthy Eating in Sustainable Food Systems (referred to as "EAT-Lancet Report"). Its peculiarity is that it is a two-year report made by 37 world-leading scientists from nutrition, agriculture, environmental science, political science and other fields from more than ten countries. The report pointed out that when the Earth’s population will reach 10 billion in 2050, and if humans want to stay within the planetary boundaries, they must take three major actions, with the most important of which being a "dietary shift" to "food of plant origin".

Since 2018, there has been a sharp increase in the number of scientific reports on food system transformation and climate change worldwide, exceeding the total number of reports in previous years. The reports issued by top scientific journals, committees, and research institutions mostly regard the transformation of the food system as (one of) the most important means to mitigate climate change without exception. Among them, the dietary shift featured with a large increase in vegetarian food and a reduction in meat consumption is essential. These findings have marked the scientific aspect of China's new vegetarian movement in the 2010s.

In the 2010s (especially in the latter half of the decade), vegetarianism gradually got to the mainstream around the world. The Economist has named 2019 the "Year of the Vegan". The European Parliament defined the meaning of "vegan" in food labelling in 2010 and introduced it to chain restaurants and supermarkets in 2015. Jacy Reese Anthis's 2018 book The End of Animal Farming claims that veganism will completely end food of animal origin around the year 2100. The concept of "alternative protein", emerged around 2016, became popular in 2019; plant-based meat, eggs and milk became prevalent in the market. As a result, a lot of capital, along with traditional meat and dairy companies, followed this trend and joined the plant protein production. These changes in the late 2010s are in line with the growing vegan movement in Europe, America and China in the 2010s and the underlying logic is very clear: helping people to reduce or even end their dependence on animal protein is a major issue for the human society in the 21st century in the face of its own existential risks.

To understand why the vegan movement has re-emerged in the 2010s, one should first recognize it as a force for change. What is it attempting to change? What exactly is wrong with our current diet that we need to change? Why does it have to change? To understand these questions, we need to apply systemic thinking to see what risks are posed by the current diet poses to human beings. As mentioned earlier, the national knowledge of environmental protection has shifted from the initial "sanitation" to a broader understanding of ecosystems. The same things applies to the food industry. If we don't go deeper into systemic thinking about the "food system", we will stop at the base of "nutritionally safe" food, thus failing to understand what the vegan movement or food revolution is all about.

The enormous health and ecological risks, as well as ethical issues, posed by the contemporary food system, are covered in a separate article. Here remains just one key question: is it worth all the risks to sustain large-scale animal farming? With all the animals we’ve raised and all the environmental and health problems we’ve caused, have we at least kept people well-fed or at least fed? Unfortunately, the fact is that 800 million people in the world go to bed hungry every day, while more than 2 billion people are obese or overweight. Americans alone spend more money on weight loss than that of the world spent on famine relief. Around the world, people who consume the most animal protein-such as meat, eggs and milk-are precisely those who need them the least; they are the over-nourished populations in developed countries and regions.

Mankind did not move from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic because we discovered new stones, or because we ran out of stones. Instead, human beings developed because of our increasing consciousness. In this sense, the shrinkage and eventually the collapse of factory farming seem inevitable - humans will finally understand that taking such a big health and ecological risk for an already over-consumed product is not only not worthy but also dangerous.

In the last two decades, vegetarianism, especially veganism (ie. not eating or using any animal products), has grown rapidly around the world and developed multiple forms, including ethical veganism, environmental veganism, feminist veganism, and new forms of religious veganism such as Jewish veganism, Jain veganism, Christian veganism, and Buddhist veganism in Europe and the United States. The Effective Altruism community, which developed out of Peter Singer's ethical thinking, has also made the reduction of farm animal suffering a major work. In China, the vegetarian movement of the 2010s has yet to present the multi-dimensional and multi-angle analysis, critique and transformation of the society that happened in the Western world, It will take time to create more spiritual resources to enrich itself and even to benefit other social sectors. The vegetarian movement in China during this period presents the following characteristics.

The first is the effort to separate itself from religious vegetarianism: the most striking feature that distinguishes the two Chinese vegetarian movements from vegetarian promotions in previous historical periods is the former’s attempt to break away from religious vegetarianism — whether it’s the leaders’ original incentives to promote the “transition into vegetarian" or the theoretical basis of the movements, both are mainly from the contemporary Western evidence-based science and philosophical ethics. As mentioned earlier, a source of the support for the Chinese vegetarian movement from the mother culture is the Chinese Buddhist tradition of vegetarianism, which is based on the principle that “be compassionate to all without exceptions and be empathetic to other’s sufferings as we are one.”Thus, a vegetarian movement attempting to separate itself from religious vegetarianism needs to address appropriately its relationship with Mahayana Buddhist tradition. While the 2010s new vegetarian movement and the concurrent development of the Buddhist community have fostered a mutual transfer in people and resources, for example, some ethical or scientific vegetarians have since converted to Buddhism, and some Buddhist disciples have become active in spreading scientific and animal-ethical vegetarianism, there are cognitive and behavioral differences between the two that are not easily understood by outsiders.

On the one hand, the traditional religious vegetarian culture is both a cultural resource and a historical burden to the vegetarian movement leaders, who are guided by science and ethics. Leaders are constantly on guard to prevent traditional and emerging religious discourses from dominating the movement again, from turning the movement into the religious communication, and from causing "misunderstanding" of the relationship between the movement and religions. For the actual advocacy, the leaders of the new movement do not employ the "let it be" approach prevalent among the Buddhists but adopt a direct advocacy for widespread promotion.

On the other hand, the "vegetarian diet" in Buddhism is only a "skillful means". Its ultimate purpose is to help sentient beings break away from the eternal suffering of reincarnation. Whether it is to solve the crisis of human existence or to reduce the suffering of animals, vegetarianism for Buddhists is only a means or "a plus", not a goal. This is the fundamental difference between religious vegetarians and contemporary scientific and ethical vegetarians.

In addition, some Buddhist practitioners also notice the "dichotomy" of "vegetarian" and "meat" in the vegetarian movement and are wary of it. According to Buddhism, clinging to "good" is more difficult to give up than clinging to "evil", and is more likely to become an obstacle to practices and "liberation". The case of the meat-eating monk Jigong and koans of the Tibetan Buddhist gurus were also passed down to practitioners as a lesson about the "attachment" to unrealistic and unjustified vegetarianism. As a result of these divergences, in practice, there is a comfortable distance between the vegetarian movement and the Buddhist community. For the Buddhist community, it is not about creating barriers for the practice of vegetarianism or making vegetarianism a "high barrier to entry" for beginners. And for the vegetarian movement, it is about how to construct a popular discourse that can influence more people, without being dominated by religious discourse.

The second is to actively build a system of popular discourse. Vocabulary is a tool for thinking and a cornerstone for building a discourse system. However, China’s new vegetarian movement (and perhaps that of countries whose official language is not English) has been struggling with vocabulary. "Su" is the Chinese character that is most frequently associated with vegetarian movement. However, as scholars analyzed, the word "Su" in non-Buddhist scholarly circles is about a "light diet", which does not completely exclude meat. Therefore, only the word "Su" in the Buddhist context is closest to the word vegetarian or vegan in the modern vegetarian movement, which is opposed to meat-eating.

However, the use of the word "Su" in a Buddhist context was not conducive to the vegetarian movement in its effort to separate itself from its religious context. Thus, the new vegetarian movement in the 2010s faced with a task of "cultural translation", which involved translating, introducing and adjusting core vocabulary all the time. It started with the transliteration of “vegan” (who do not eat or use any animal products) as "Weigen," which co-exist with other expressions "Quansu" (whole-vegetarian), "Chunsu" (pure-vegetarian), and Buddhist "Jingsu" (clean-vegetarian). Finally, the term "Chunsu" prevailed. This phenomenon is not unique to Chinese-speaking regions. Even in India, which has a long history of vegetarianism, the Hindi term "pure vegetarian" had to be coined as a counterpart to the word "vegan" to distinguish it from the Indian subcontinent's vegetarian tradition that does not exclude dairy products. The term "Jingsu" is a further attempt to remove foods, such as onions, garlic and leeks, considered "agitative" by Buddhists from the list of “clean-vegetarian” foods.

In the latter half of the 2010s, the more popular term "plant-based food" in the English-speaking world, referring to a plant-based diet that does not include meat, eggs and milk, was soon translated into "Shushi" (a more traditional term used by the vegetarian movement in the early Republic of China), “plant-based diet”, and “plant-derived diet” (which also led to the term "plant-based industry" around 2019, referring to the increasingly popular production of plant-based meat products).

But others have pointed out the "flaws" of the term - firstly, it refers to a "vegetarian-based" diet, not 100% vegan. Secondly, the fungal foods popular with vegans aren't strictly "plants". The word corresponds to animal protein. This concept, which is based entirely on Western nutrition (the term for protein), makes it very convenient for Chinese speakers to refer to animal foods like meat, egg and milk, and thus avoiding the one-sidedness of just saying "meat". After all, the egg and poultry industry has the largest population of farmed land animals and the dairy industry has a staggering carbon footprint and disregard for animal welfare.

Another challenge in establishing a new discourse is the binary opposition of the "vegetarian" discourse. In China's "vegetarian" tradition, secular scholarly culture and even Mahayana Buddhism do not hold vegetarianism and meat (or "Xing") in absolute opposition to each other (the popular image of the Buddhist monk Jigong is one example). The two waves of vegetarian movements in China in the 1910s and 2010s, like the international vegetarian movement of the same period, were based on the absolute dichotomy between "vegetarian food" and "meat" (later called "animal protein"). In the early stages of the movement, it was easy to establish and consolidate one's own camp. But as the movements progressed, the division was likely to lead to a confrontation of views and emotions, which was not conducive to achieving the movement's goals of improving public health, slowing ecological degradation and reducing animal suffering.

Therefore, as one of the main participants of the movement, I established the "Good Food Fund" at the China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation in 2017, in an attempt to minimize the conflict and push the movement towards a more sustainable direction. "Good Food" dissolves the dichotomy of "vegetarian food": "good food" refers to food that is healthy, sustainable and good, in which case "vegetarian" is not necessarily "good food". For example. Coca-Cola (vegan, but unhealthy) and plant-based foods that are ecologically unsustainable and harmful to local communities during production (such as palm oil, which destroys rainforests in South-East Asia, and avocados from South America). On the other hand, "good food" is not the same as vegetarian food, thus leaving valuable space for animal agriculture to improve animal welfare and reduce animal suffering in a timely manner.

The third is the new vegetarian movement and the "transformation of the food system". The 2010s new vegetarian movement in China has not yet positioned itself in a larger political, socio-economic and cultural context, so there is still much room for improvement in terms of resource mobilization and social support. In order to connect more stakeholders, future promoters should seek to avoid the stubbornness, controversy and confrontation that can result from advocating for a single issue.

Just as the promotion of environmental protection requires systemic thinking, if the promotion of vegetarian food, which is based on contemporary science and ethics, cannot establish systemic thinking by linking it to the "transformation of the food system", it will inevitably fall into the trap of "using your spear against your shield" and will be difficult to justify itself. Current mainstream Western nutritional research, ecological agriculture, environmental science and food security concerns all support a global reduction in the production and consumption of animal protein (mainly intensive industrial farming), but these arguments are not the same as advocating vegetarianism for all. Even though there is no doubt that industrial farming should be abolished from a bioethical perspective, there is much room for discussion between the abolition of industrial farming and the complete elimination of all livestock farming from agricultural production.

The promotion of new vegetarian movements in the 2010s is relatively homogenous, focusing on consumer education and transformation, and almost all through social media campaigns and the establishment of vegetarian restaurants. The campaigns focused on post-80s and post-90s vegetarians, and took advantage of the emerging WeChat official accounts, which led to a number of vegetarianism accounts that influence public perception. The restaurants that served mostly post-50s to post-70s attempted to guide public consumption through the establishment of a "vegetarian industry".

The above two are the paths taken by almost all vegetarians in the 2010s, resulting in both successes and challenges. The success of the WeChat official account lies in the shaping of public's perception of vegetarianism outside of religious discourses. The challenge is that the daily output of new content would create a bottleneck for producing new content, and it becomes difficult to break out of a fixed silo. The popularity of vegetarian restaurants has increased the variety of vegetarian food and made it easier for vegetarians to socialize. However, once opening vegetarian restaurants become the only way for many people to participate in the promotion of vegetarian food, it is inevitable that a large number of vegetarian restaurants will operate poorly everywhere, leading to a negative impact on the confidence and enthusiasm of both the public and investors.

Interestingly, both forms of the new vegetarian movement have similarity with the first 1910s vegetarian movement 100 years ago. For example, the promoters of the time, Ding Fubao and American doctors Harry Miller and Arthur Selmon, promoted vegetarianism by writing books (The Way to Health and Health and Longevity), where Wu Lien-teh wrote a preface to praise Miller's efforts and contributions and argue that vegetarianism was in line with Chinese customs. As another example, in 1910 Li Shizeng and Wu Tingfang's "Dharmadhatu Micaili" vegetarian restaurant and the Nanyang Brothers Tobacco, Jane's Kung Tak Lin vegetarian restaurant became Shanghai's modern restaurants. Millar later served as a director of the Shanghai Sanatorium and developed vegetarian recipes, which were implemented in the sanatorium. He taught how to make whole wheat bread, introduced Chinese vegetarian elements such as tofu and advocated for making vegetarian food more palatable.

Even the promotion of "vegetarian food in universities" by students - who were aimed to establish "vegetarian sections" and "vegetarian cafeterias" on campuses - in the 2010s, can find their predecessor 100 years ago. In November 1917, a Peking University student wrote a letter to Cai Yuanpei, who was the President of the University by then, calling for the opening of a vegetarian restaurant to promote a “more frugal and hygienic” vegetarian diet on campus.

The reason why I switched from vegetarianism to the "Good Food" movement is to break through the limitations of the two vegetarian movements of the 1910s and 2010s. In the 1910s, liberal intellectuals in China generally looked down on farmers and agriculture, believing that they were responsible for China's slow economic development. In the 2010s, the rebuilding of the countryside seems to have become a global trend. The thought of "eco-agriculture" and "young returnees to rural areas" has emerged in China. Then the trend and thought, like the vegetarian movement, are responses to the crisis of human existence.

Therefore, we launched the first Good Food Summit in Yangzhou in 2017, with the goal of creating dialogue, understanding, interaction and collaboration between people from ecological agriculture and vegetarian movements, in an effort to promote the transformation of the food system togther. The annual Good Food Summit has since been joined by a variety of stakeholders, including scholars, chefs, food service organizations and restaurants. The annual “Good Food Festival” and the New Year's Healthy and Sustainable Menu were designed for discovering and cultivating "Good Food Chefs". We co-founded the Food Forward Forum with Yale University, Harvard and other universities. We also adapted food curriculums for Chinese audience developed by the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future. During the 2020 pandemic, the Good Food Fund has added a new area of work on food policy. These efforts are intended to move the vegetarian movement away from a single-issue, single-path approach and to find its place in the systemic transformation of the food system.

Main Reverence

梁其姿(Angela Ki Che Leung),To Build or to Transform Vegetarian China - Two Republican Projects. MORAL FOODS: THE CONSTRUCTION OF NUTRITION AND HEALTH IN MODERN ASIA, Edited by Angela Ki Che Leung and Melissa L. Caldwell. 2019 University of Hawai‘i Press.

Reverence

中国绿发会良食基金《中国肉食地图》

“何以为食”公众号

素食雷达公众号

Rod Preece, Sins of the Flesh: A History of Ethical Vegetarian Thought, Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2008, 12.

^ "Definition of VEGETABLE". www.merriam-webster.com.

^ Davis, John (1 June 2011). "The Vegetus Myth". VegSource. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018. Vegetarian can equally be seen as derived from the late Latin 'vegetabile' – meaning plant – as in Regnum Vegetabile / Plant Kingdom. Hence vegetable, vegetation – and vegetarian. Though others suggest that 'vegetable' itself is derived from 'vegetus'. But it's very unlikely that the originators went through all that either – they really did just join 'vegetable+arian', as the dictionaries have said all along.

中華百科全書:主義:http://ap6.pccu.edu.tw/Encyclopedia/data.asp?id=247

Sabaté, Joan (September 2003). "The contribution of vegetarian diets to health and disease: a paradigm shift?". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 78 (3): 502S–507S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/78.3.502S. PMID 12936940.

^ American Dietetic Association; Dietitians of Canada (June 2003). "Position of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada: Vegetarian diets". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 103 (6): 748–765. doi:10.1053/jada.2003.50142. PMID 12778049.

Eat less meat: UN climate-change report calls for change to human diet

The report on global land use and agriculture comes amid accelerating deforestation in the Amazon. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-02409-7

IPCC SPECIAL REPORT

Climate Change and Land https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/

EAT-柳叶刀报告

https://eatforum.org/eat-lancet-commission/eat-lancet-commission-summary-report/

"Vegan Diets Become More Popular, More Mainstream". CBS News. Associated Press. 5 January 2011. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

Nijjar, Raman (4 June 2011). "From pro athletes to CEOs and doughnut cravers, the rise of the vegan diet". CBC News. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

Molloy, Antonia (31 December 2013). "No meat, no dairy, no problem: is 2014 the year vegans become mainstream?". The Independent. Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

^ Jump up to:a b c d Tancock, Kat (13 January 2015). "Vegan cuisine moves into the mainstream – and it's actually delicious". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

Crawford, Elizabeth (17 March 2015). "Vegan is going mainstream, trend data suggests". FoodNavigator-USA. William Reed Business Media. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

Oberst, Lindsay (18 January 2018). "Why the Global Rise in Vegan and Plant-Based Eating Isn't A Fad (600% Increase in U.S. Vegans + Other Astounding Stats)". Future of Food. Food Revolution Network. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

Jones-Evans, Dylan (24 January 2018). "The rise and rise of veganism and a global market worth billions". WalesOnline. Media Wales. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

Nick Pendergrast, "Environmental Concerns and the Mainstreaming of Veganism", in T. Raphaely (ed.), Impact of Meat Consumption on Health and Environmental Sustainability, IGI Global, 2015, 106.

^ Jump up to:a b Hancox, Dan (1 April 2018). "The unstoppable rise of veganism: how a fringe movement went mainstream". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

^ Parker, John. "The year of the vegan". The Economist. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

^ "European Parliament legislative resolution of 16 June 2010", European Parliament: "The term 'vegan' shall not be applied to foods that are, or are made from or with the aid of, animals or animal products, including products from living animals."

^ Rynn Berry, "Veganism", The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink, Oxford University Press, 2007, 604–605

文汇 2019-05-14

功德林可能并非上海第一个素菜馆——摩登素食主义在上海|一点历史

http://app.myzaker.com/news/article.php?pk=5cda714a77ac64050d279e12